Client Articles: Beyond Teams

Invention As A Practice Theory For Organizational Transformation

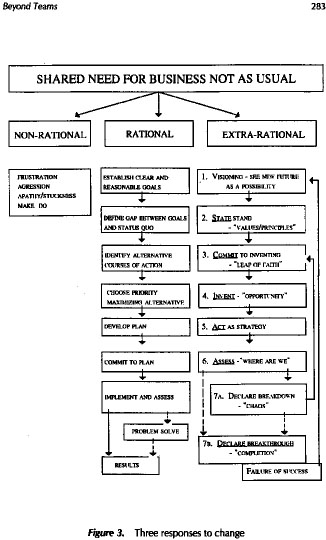

What process did people go through to invent their organization? Our goal is to present a practice theory or action model that people in Magma would say described accurately how they have transformed their organization. This "theory" or guide to action emerged from our reflecting on the stories people told about their generative events-especially stories about breakthroughs. Conversations with groups of activists helped to clarify and operationalize the theory. It evolved until people agreed that it described the process they went through in envisioning and realizing new possibilities. The model of Magma's invention-based change has subsequently been used in training courses to promote leadership for invention. This model can be more meaningful if contrasted with two other models of how organizations respond to change (see Figure 3).

Pressures for change can come from such factors as crisis, challenge, vision, strategy, etc., or a combination of these. Such pressures are increasingly widespread, well documented, and problematic. Generally, organizations in America need to radically change their normal ways of thinking about and doing business. Even the popular business press is calling for new thinking and "business NOT as usual." Different organizations respond differently to this need. Not 0 organizational responses are rational. The models in Figure 3 are based on three quite different ways of coping with these pressures for change:

These three models separate out reactions or responses that in practice are highly intermingled, so presenting them here as completely separate is simply an analytical aid. All three can be found in the record of events at Magma.

Pressures for change can come from such factors as crisis, challenge, vision, strategy, etc., or a combination of these. Such pressures are increasingly widespread, well documented, and problematic. Generally, organizations in America need to radically change their normal ways of thinking about and doing business. Even the popular business press is calling for new thinking and "business NOT as usual." Different organizations respond differently to this need. Not 0 organizational responses are rational. The models in Figure 3 are based on three quite different ways of coping with these pressures for change:

- Nonrational (i.e., not aimed at organizational adaptation and effectiveness; emotional; cathartic; therapeutic or "rational" in some way not consistent with organizational goals);

- Rational (i.e., helps a system to cope with pressures for change and increase effectiveness and adaptability within existing paradigms; change within a given state or set of system properties; purposeful; programmatic.);

- Extrarational (i.e., beyond linear coping within a given state or paradigm; metamorphosis; extrarational as in extraordinary or beyond the ordinary).

These three models separate out reactions or responses that in practice are highly intermingled, so presenting them here as completely separate is simply an analytical aid. All three can be found in the record of events at Magma.

The Magma Model of Invention-Based Change

Nonrational, emotional reactions to pressures for change can be seen in company-union relations up to the fall of 1989. Interviews with key leaders in the company and the unions in mid-1989 revealed that virtually all communication between the two parties occurred in relation to formal provisions of the contract. The grievance procedure was the primary means of communication between labor and management. Industrial relations were not just adversarial. They were solidly stuck in conflict and enmity, and they seemed to be deteriorating.

In many of our conversations, activists from both union and management described the contract negotiations completed in mid-1989 as particularly tough, bruising, and even at times violent. Some saw the unions and the company as locked in a life or death struggle. The company saw itself in such a difficult financial situation that it was operating in a survival mode. The union members felt that the company was trying to break the unions. Union leaders reported being so angry and frustrated that the feeling was "if they are out to bust the union, well take them down with us." The final agreement contained a provision for creating a labor-management cooperation committee, although no one was sure what, if anything, it would mean in practice.

If the conventional or "rational" model of change (see Figure 3) were followed here, consultants would bring together representatives for labor and management to develop a plan for increasing cooperation. The plan would be based on the gap between how people wanted things to be and how they were at present. The consultants and participants would identify alternative ways of closing the gap, select the one that seemed to maximize goals, and develop a reasonable plan of action. In this model, commitment to act follows naturally, because one has a reasonable course of action to follow. It is reasonable and understood, in part, because people who are to implement it have been involved in designing it. Should difficulties arise in implementation, they are "problem-solved" (i.e., one repeats the rational process of defining the problem clearly; identifying alternative solutions; choosing the one that maximizes one's preferences; etc.). A well planned project, however, should have few problems. Hence the tendency in this model is to think linearly from goal to plan to commitment to implementation to results.

In many of our conversations, activists from both union and management described the contract negotiations completed in mid-1989 as particularly tough, bruising, and even at times violent. Some saw the unions and the company as locked in a life or death struggle. The company saw itself in such a difficult financial situation that it was operating in a survival mode. The union members felt that the company was trying to break the unions. Union leaders reported being so angry and frustrated that the feeling was "if they are out to bust the union, well take them down with us." The final agreement contained a provision for creating a labor-management cooperation committee, although no one was sure what, if anything, it would mean in practice.

If the conventional or "rational" model of change (see Figure 3) were followed here, consultants would bring together representatives for labor and management to develop a plan for increasing cooperation. The plan would be based on the gap between how people wanted things to be and how they were at present. The consultants and participants would identify alternative ways of closing the gap, select the one that seemed to maximize goals, and develop a reasonable plan of action. In this model, commitment to act follows naturally, because one has a reasonable course of action to follow. It is reasonable and understood, in part, because people who are to implement it have been involved in designing it. Should difficulties arise in implementation, they are "problem-solved" (i.e., one repeats the rational process of defining the problem clearly; identifying alternative solutions; choosing the one that maximizes one's preferences; etc.). A well planned project, however, should have few problems. Hence the tendency in this model is to think linearly from goal to plan to commitment to implementation to results.

The Scottsdale meeting followed a different model. It was based on participants inventing what they needed. Here consultant intervention aimed at client invention. The way the Scottsdale model worked seemed to set a pattern for other change efforts at Magma. We can see the extra-rational foundations of action in Sunspace and the breakthrough projects.

The third model, from the Magma experience, is "extra" rational in not being limited to what is rational within a single frame or paradigm or mental set. One is limited by what one defines as possible; by how one orients oneself. One of the common phrases in Magma's culture of invention is questioning one's own orienting frame. The idea is to be able to think outside of "the box" or the "9 dots" to see what is possible and invent ways to make it happen.

The Magma change process seems to tap into other sources of energy and action than what existing motivation theory can explain. People are willing to "walk into the unknown" together. Inspiration seems to be a way of doing business. People talk about a "leap of faith." One person described the change process as 'real scary," because it went beyond "getting out of the box." It was getting out of the box and having the box disappear: there was no box to go back to! Magma's practice theory for change calls for deep personal commitment, a challenge to personal identity, and existential courage. Getting involved, at least for these activitists, has been no small matter.

The Magma model begins with seeing a new future as a possibility. The key term is "possibility" which can be vague initially. It can mean realizing that one no longer thinks something is impossible. Some described it as a light bulb turning on or a sudden insight. "Things could be very different around here." "At first I never thought we could do it." In the terminology defined for this inquiry, this is a "generative event." A person's engagement in the process of inventing a new future starts here. What seemed to become clear for people was what they could uniquely contribute. The term "vision" means ideals and values, but at Magma these are specified in terms of clear, measurable business goals. What would be unknown is how these business results are to be produced. Intuitively, however, one senses that somehow it could be done, and one is drawn into an attempt. Together, the combination of crystal clear ends and open-ended, "trial and error" means, defines a form of work that looks more like research than production and creates an arena for invention.

The next step is to state where one stands. People take a public stand in declaring the principles and values that will guide their actions. This helps clarify and support the unique contributions that are being made. The stand is an expression of personal commitment. And in taking a stand, people make a commitment to get into action. The catch is that there is no plan. The commitment is to start inventing how they would progress toward what they are committed to. There is no predetermined strategy of how they will reach their goal. The commitment is a leap of faith and a promise to invent what is necessary while underway. Their strategy is getting into action (planning on the run or "aim, fire, ready?).

This could be seen as a high risk strategy. But from a base of committed action, barriers or difficulties are not problems to be avoided but merely interruptions in progress. These difficulties could be evident when actual results are compared to promised results or when things get stopped. They are a break in the action. These "breakdowns" are sought out, because they are useful in identifying what needs to be changed in order to continue the action and progress towards one's vision. Thus the people involved are always in charge (on top) of their change process: they seek out and declare breakdowns. "Breakdowns are exciting!" declared one union activist with a big smile and twinkle in his eye. A breakdown does not happen to people; they create it by declaration. The chaos implicit in a breakdown is also not threatening, because people rely on their commitment to continue the action (hence the arrow in Figure 3 from breakdowns to commitment). They face (i.e., go through, rather than around) the uncertainty and ambiguity inherent in a break in the action. Thus breakdowns become a rich opportunity to learn and discover what might not have been possible otherwise, and this in turn leads to more significant breakthroughs.

Several of the activists who helped develop this model pointed out that completing a breakthrough project did not end there. There was always the failure of success in that the more significant the breakthrough the more likely it would later lead to new difficulties. This is included in the model with the arrow leading from "breakthrough" back up to "visioning."

Introduction

Magma-A: Part I

Magma-A: Part II

Research Issues & Designs

Findings: Generating A Culture of Invention

Invention As A Practice Theory For Organizational Transformation

Contrasting Organization Development And Transformation

Summary, Acknowlegements And References

The third model, from the Magma experience, is "extra" rational in not being limited to what is rational within a single frame or paradigm or mental set. One is limited by what one defines as possible; by how one orients oneself. One of the common phrases in Magma's culture of invention is questioning one's own orienting frame. The idea is to be able to think outside of "the box" or the "9 dots" to see what is possible and invent ways to make it happen.

The Magma change process seems to tap into other sources of energy and action than what existing motivation theory can explain. People are willing to "walk into the unknown" together. Inspiration seems to be a way of doing business. People talk about a "leap of faith." One person described the change process as 'real scary," because it went beyond "getting out of the box." It was getting out of the box and having the box disappear: there was no box to go back to! Magma's practice theory for change calls for deep personal commitment, a challenge to personal identity, and existential courage. Getting involved, at least for these activitists, has been no small matter.

The Magma model begins with seeing a new future as a possibility. The key term is "possibility" which can be vague initially. It can mean realizing that one no longer thinks something is impossible. Some described it as a light bulb turning on or a sudden insight. "Things could be very different around here." "At first I never thought we could do it." In the terminology defined for this inquiry, this is a "generative event." A person's engagement in the process of inventing a new future starts here. What seemed to become clear for people was what they could uniquely contribute. The term "vision" means ideals and values, but at Magma these are specified in terms of clear, measurable business goals. What would be unknown is how these business results are to be produced. Intuitively, however, one senses that somehow it could be done, and one is drawn into an attempt. Together, the combination of crystal clear ends and open-ended, "trial and error" means, defines a form of work that looks more like research than production and creates an arena for invention.

The next step is to state where one stands. People take a public stand in declaring the principles and values that will guide their actions. This helps clarify and support the unique contributions that are being made. The stand is an expression of personal commitment. And in taking a stand, people make a commitment to get into action. The catch is that there is no plan. The commitment is to start inventing how they would progress toward what they are committed to. There is no predetermined strategy of how they will reach their goal. The commitment is a leap of faith and a promise to invent what is necessary while underway. Their strategy is getting into action (planning on the run or "aim, fire, ready?).

This could be seen as a high risk strategy. But from a base of committed action, barriers or difficulties are not problems to be avoided but merely interruptions in progress. These difficulties could be evident when actual results are compared to promised results or when things get stopped. They are a break in the action. These "breakdowns" are sought out, because they are useful in identifying what needs to be changed in order to continue the action and progress towards one's vision. Thus the people involved are always in charge (on top) of their change process: they seek out and declare breakdowns. "Breakdowns are exciting!" declared one union activist with a big smile and twinkle in his eye. A breakdown does not happen to people; they create it by declaration. The chaos implicit in a breakdown is also not threatening, because people rely on their commitment to continue the action (hence the arrow in Figure 3 from breakdowns to commitment). They face (i.e., go through, rather than around) the uncertainty and ambiguity inherent in a break in the action. Thus breakdowns become a rich opportunity to learn and discover what might not have been possible otherwise, and this in turn leads to more significant breakthroughs.

Several of the activists who helped develop this model pointed out that completing a breakthrough project did not end there. There was always the failure of success in that the more significant the breakthrough the more likely it would later lead to new difficulties. This is included in the model with the arrow leading from "breakthrough" back up to "visioning."

Introduction

Magma-A: Part I

Magma-A: Part II

Research Issues & Designs

Findings: Generating A Culture of Invention

Invention As A Practice Theory For Organizational Transformation

Contrasting Organization Development And Transformation

Summary, Acknowlegements And References